Pippa Oldfield at the site of Elizabeth Beachbard's grave in Tangipahoa, Louisiana © John Oxley

I always suspected that women took photographs during the American Civil War (1861–1865), but it wasn’t until a few years ago that I found some brief references to a Mrs Beachbard. This enterprising woman made ambrotype portraits of soldiers at a Confederate military camp in rural Louisiana.

When I began my research, very little was known about Elizabeth Beachbard. She had worked as a photographer in New Orleans in the late 1850s, and then at Camp Moore in Tangipahoa in 1861, where she died and was buried.

But I wanted to know more than these bare facts.

I spent several years investigating her life, following a trail that was by turns frustrating, unexpected, and illuminating. I travelled to Louisiana to identify the location of her first photography studio in downtown New Orleans, and visited the site of Camp Moore and her gravestone nearby. I delved into archives, talked to curators and consulted collectors who owned the only two surviving examples of her work. I became completely obsessed with genealogical records, military documents and newspaper tittle-tattle. I investigated the photography scene in New Orleans, and discovered how women operated as professional photographers in the mid 19th century.

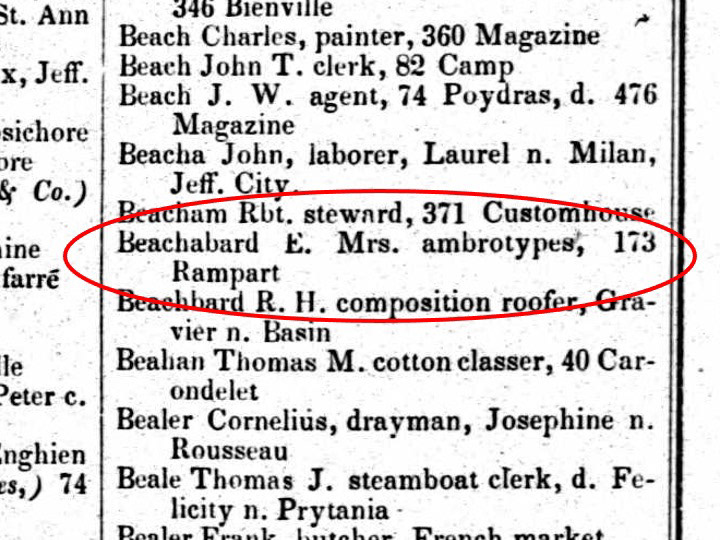

Trade listing for Elizabeth Beachbard's business in Gardner’s New Orleans Directory 1861

The site of Elizabeth Beachbard's ambrotype studio, S. Rampart Street in New Orleans © Pippa Oldfield

Elizabeth Beachbard, A.V. Going, Independent Rangers, Camp Moore, 18 August 1861. Sixth plate ambrotype in case. © Collection of J. Dale West.

Finally, I was able to produce the first detailed biography and critical assessment of Elizabeth Beachbard's life and work, published in peer-reviewed journal History of Photography.

It's a tale of twists and turns, including a measles epidemic, court cases, bigamy, and a devastating fire. One of my most exciting finds was new evidence for an ambrotype hitherto unattributed to Beachbard, which constitutes only the third surviving example of her work.

Like many women, Elizabeth Beachbard would not be considered a war photographer in the conventional sense, and her work has not entered the canon. However, I argue, she worked in a military arena, made pictures of soldiers in wartime, and lost her life in the activity.

She deserves to be remembered as a pioneering figure in the history of women’s photography; perhaps, even, she could lay claim to being considered America’s earliest identifiable female photographer of war.

Mrs Beachbard's studio at Camp Moore was a 'shanty', similar to the one pictured here. Bergstresser Brothers of Pennsylvania, c.1863-4 © MOLLUS Collection, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center.

Camp Moore, where Mrs Beachbard worked from May 1861 until her death in November that year. © Pippa Oldfield

Elizabeth Beachbard, Edward Lilley, Camp Moore, 5 July 1861. Ambrotype in case. © Collection of Glen Cangelosi.

Read the full article in History of Photography.

My thanks to the Peter Palmquist Memorial Fund for supporting this research, and to the numerous archivists, curators, collectors and scholars who generously shared their knowledge.